Prioritizing Teaching & Learning: OIP-OLAC provides system-wide foundation for effective use of MTSS on behalf of each child

When Eugene Blalock took the helm of the North College Hill City School District (NCH) six years ago, he took time to observe what the district was doing to support and sustain improvements in teaching and learning. He was particularly interested to identify the systems (e.g., structures and processes) that were in place. "That first year, I looked and listened and realized that there weren't any solid systems in place. I had come from a district steeped in the Ohio Improvement Process (OIP) and had a pretty good understanding of the OIP and how great it is," explained Superintendent Blalock.

Recognizing the need for better supports, Blalock took action. "The following year I moved Ms. Garton, then a building-level administrator, to central office to serve as Director of Teaching and Learning. We were of one accord in terms of understanding the OIP and the importance of systems. And, we started putting the system in place piece by piece," added Blalock.

The North College Hill City School District (NCH)

Located in urban Cincinnati, NCH serves about 1,300 students across four buildings (NCH Elementary School, NCH Middle School, NCH High School, and the alternative Trojan Way Learning Center). Approximately 80% of NCH's student population is Black, virtually all students — 99.9% — are characterized as "economically disadvantaged" by the state, and almost a quarter of them (i.e., 23.7%) are identified as students with disabilities receiving special education services.

Allness: All Children, All Adults, All Levels

Blalock (pictured here) and Garton soon realized that “systems thinking” was what the district really needed. Systems thinking is “a set of habits or practices within a framework that is based on the belief that the component parts of a system can be best understood within the context of relationships with each other and with other systems, rather than in isolation. Systems thinking focuses on cyclical, rather than linear cause and effect, relationships.” (Barr, 2012, p. 1).

Systems thinking begins with the right vision, and the right vision for NCH, in Blalock and Garton’s view, was “allness.” For these two district leaders, all really does mean all, both in terms of meeting the needs of all students and in involving all faculty and staff at all levels of the system in the core work of the district to improve teaching and learning.

"Allness," or being intentional in affecting all teachers and all students, is one of four criteria necessary for whole system reform and system-wide sucess, according to Michael Fullan, who is well known worldwide as a leader in educational leadership and reform.

Throughout much of his writing (e.g., 2011, 2021), Fullan talks about the importance of seeing and working to improve systems in their entirety, that is, of identifying and using the right drivers for whole system success. In more recent work, Fullan and colleagues discuss the value of coherence as a driver of systems improvement, noting the negative impact of fragmented, piecemeal approaches to reform.

North College Hill City School District District Strategic One Plan, 2019-2022

Overarching Emphasis: to improve administrator shared leadership, teacher engagement capacity, and data acquisition and use through focused, sustained, and embedded professional learning and coaching in evidence-based practices and interventions with a strong emphasis on using multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) for academics, behavior, and attendance.

The OIP according to Blalock and Garton is one of a handful of “right drivers” of true improvement. "One thing that is really significant that moved us drastically with the OIP process is that we always believed in it and we always wanted to have it happen at all levels," said Michelle Garton, NCH Director of Teaching and Learning.

The OIP supports NCH's focused plan for districtwide improvement by emphasizing shared leadership, teacher engagement, effective data use, high-quality professional development including coaching, and the use of multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) — elements designed to build the capacity of all educators to use evidence-based, inclusive instructional practices that improve learning opportunities and achievement for each student, irrespective of the student's classroom or school assignment. Family-community engagement is another “right driver.” Blalock and Garton are committed to working with families and the larger community to ensure that each student experiences success every day.

The district's overarching emphasis, as stated in its District Strategic One Plan, and its core set of beliefs (listed below) reflect a deep commitment to engaging all aspects of the education community in improving learning outcomes:

- Education is the responsibility of the entire community.

- All individuals have value.

- Effective two-way communication is essential for trust and understanding.

- A safe, caring, respectful environment is essential for learning.

- The entire school community has the power to create an environment with opportunities for all individuals to succeed.

- Every child can learn and be challenged to pursue an excellent education.

OIP as the foundation for instructional improvement. Ensuring that each of NCH's 1,300+ children experiences success requires what Garton calls diligent purpose in continually working toward quality, consistency, and coherence in the instruction that is provided across the district.

Equity means that “each child has access to relevant and challenging academic experiences and educational resources necessary for success across race, gender, ethnicity, language, disability, family background, and/or income.”

Each Child, Our Future: Ohio's Strategic Plan for Education (2019-2024), p. 8

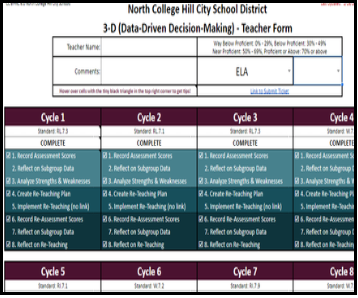

"In using the OIP, I think a lot of times, people miss steps 4 and 5 — you have relevant information but then do you know how to use it? We've created systems, dashboards that support teachers to not only provide intervention, but to reteach things that students are missing. That's where equity comes into play. You're drilling down, giving each student what they need based on what the data say. For example, you might go from whole-group to small-group instruction based on the needs of particular students, and then reteach specific skills in a different fashion to address individual student needs," said Blalock.

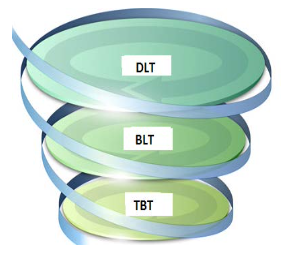

NCH uses aligned leadership team structures in keeping with Ohio's Leadership Development Framework (2022): a district leadership team (DLT), building leadership teams (BLTs), and teacher-based teams (TBTs), which the district calls GLTs or grade-level teams. The DLT meets monthly, BLTs meet about two times each month, and GLTs meet weekly to every other week.

In addition to the DLT-BLT-GLT team structure, NCH holds data team meetings by grade level every six weeks, followed by problem-solving team meetings the "7th week" - that is, the week following the data team meeting.

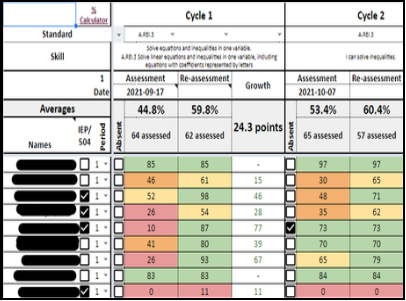

According to elementary Instructional Coach Anne Marie Barth, the data team meetings are designed to look at the effects of whatever interventions are being provided to individual children in order to help the team answer the question, "is each child progressing?"

Data are recorded using a data tracker that Jess Lane, District Data Coordinator, developed for systemwide use. Lane, a former high school math teacher, also serves as mathematics instructional coach at the middle and high school levels. Using web-based tools, like the data tracker and data dashboards, means teachers no longer have to fill out forms on their own and "do the math," said Lane. "They can very easily look at the data to determine what student groups need to be given a bit more intervention within the classroom; this really supports our Tier 1 instruction," added Lane.

Emily Mulcahey, secondary Instructional Coach, who taught in the district for 21 years before becoming a coach, recalled the considerable time needed for using paper forms and doing calculations as a major drawback of the OIP. "Now, teachers can focus on what the data are telling them. We're shifting to a mindset of 'we use our data to help us drive instruction, to help us make good decisions,'" explained Mulcahey. Garton, Barth, Lane, Mulcahey, and Kelly Knauer (also an elementary-level Instructional Coach) form the district's Teaching and Learning Team (pictured below). The team helps all teachers provide strong core instruction to all children and intervention to children who need it. "Whether it's a classroom shift in instruction or whether it's helping to find resources for intervention, we help facilitate that process," said Mulcahey about Team's role.

Changing the conversation. Resisting the tendency to stop intervention too early, or to not provide it at all, involved a deep learning curve, according to Barth. "We'd hear a lot about the child being sick or being absent, but if we see that the intervention is working, we're going to continue to provide it until we see that it is effective enough."

For children receiving more intensive intervention, teachers collect data weekly and enter them into the dashboard. Progress is reviewed during data team meetings, which include members of the GLT, the administrator, and instructional coach.

Data for students for whom intervention does not appear to be working (e.g., ineffective growth after two cycles of the same intervention) are then reviewed by the problem-solving team (aka the MTSS building team) -- a large team composed of general education teachers, intervention specialists, related services personnel, Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs), school counselors, administrators, and instructional coaches.

“We realized a lot of our teachers were saying, 'these kids are failing and it's the same kids that are failing.' When we got down to the core of it, it was sometimes more of an SEL issue," said Barth who credits the OIP process and embedded problem-solving team approach with changing the conversation in NCH.

Instead of viewing children as the cause of failure, educators are now asking different questions: 'Is it the instruction we're providing? Is it the curriculum? Is it the environment?

MTSS: A Way of Thinking

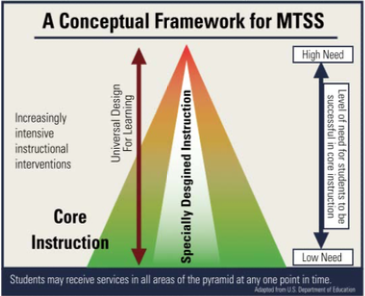

Multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) refers to the integration of academic and behavioral tiered models (i.e., response to intervention or RTI and schoolwide positive behavioral supports or SWPBS) into "one coherent, strategically combined system meant to address multiple domains or content areas in education (e.g., literacy and social-emotional competence)." (McIntosh & Goodman, 2016, p. 5).

According to Garton, "MTSS is a way of thinking; it's the idea of helping every student every day. It's not another initiative. The OIP is the process through which we make that thinking happen, where we have the learning occur.”

Mulcahey agreed, noting that "MTSS is not 'something extra;' it's what you, as a teacher, were always doing." "The basis for MTSS, or our foundation, is the five-step OIP process and the teams - starting with the District Leadership Team where every building is represented," added Blalock.

The use of an MTSS model, as described in Each Child Means Each Child: Ohio's Plan to Improve Learning Experiences and Outcomes for Students with Disabilities (Ohio Department of Education, 2021), is to "get to the problem early." In other words, the purpose of MTSS is to support the use of age-appropriate core instruction that "can lead to improved student achievement, reduce the need for punitive discipline that removes students from the learning environment and mitigate the likelihood of overidentifying students with disabilities." (p. 22). A conceptual framework for MTSS, adapted from the US Department of Education, is provided in Each Child Means Each Child.

Tiers represent instruction and supports, NOT categories of students. A common misconception involves the assignment of students, by programmatic category, to tiers in the MTSS model (e.g., special education = tier 3). In Each Child Means Each Child (p. 23), as in NCH's use of MTSS:

- Tier 1 refers to universal supports and instruction (i.e., core instruction) provided to all students.

- Tier 2 refers to more targeted interventions provided to students who need them in concert with, not instead of, Tier 1 core instruction (e.g., greater intensity of instruction for an extended period often provided through small-group instruction and based on needs of each student).

- Tier 3 refers to intensive supports that are required beyond the instruction, interventions, or supports provided through Tier 1 and 2 (typically provided individually).

"Because the process is about all students, when we're talking about providing interventions; we're not looking at them as special education interventions. The process itself allows us to take a really good look at the student and we're not over-identifying students any longer. In the past, the moment the child struggled, we might have said, 'oh, this child needs special education.' Now, we're looking at the entire child and going through the process to find out what interventions or what support that child may need and putting in a stopgap before the child is automatically tested. We're not pulling kids out based on preconceived notions that the child has a disability," explained Blalock.

"We have considerably fewer students being referred for testing because teams are looking at data and communicating back and forth through the data dashboards. In the past, it was difficult for teachers to know what other teachers were doing and they wondered if we were doing enough," said Garton. "Now, teachers are saying 'it's working, wow, keep going,' instead of 'we have to get this kid help right now; we need to get them identified,'" added Garton.

"I've been in three meetings this year that involved referrals from parents who believed their child had a disability. We were able to share the data, and instead explain that we didn't suspect a disability and were able to target just the skill deficit and show that we were actually providing the support they needed, explained Barth.

Mulcahey relayed a similar experience, reflecting the increasing understanding on the part of teachers that placement in special education is not the only recourse available for providing needed support. "The idea that I, as a classroom general education teacher, can provide intervention is a mindshift. It used to be 'okay, well, if they're not getting it the way I'm teaching it, then it's somebody else's responsibility.'" said Mulcahey. Increasingly, teachers are understanding that they "are capable of teaching in a different way or providing an intervention. Part of our coaching is helping them to think about how they can shift their instruction, and use other instructional strategies that might be more successful, in meeting needs of children that are struggling," she added.

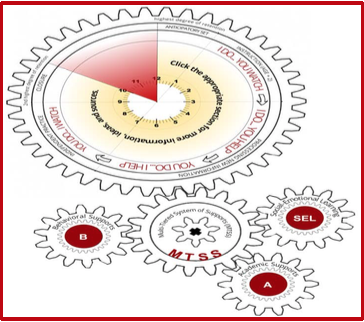

NCH is intentional in bringing important parts of its work together, as illustrated in the graphics above, the first from the district and the second from Each Child Means Each Child. "Academic supports, behavioral supports, and social-emotional learning supports are integrated," explained Lane. The Teaching & Learning Team is also intentional in investigating and using high-quality instructional and curricular materials, that is, programs that have "high evidence.”

All On Board: The NCH Way

Under Garton's leadership, NCH developed a staff handbook to establish a foundation for MTSS use within the larger OIP-OLAC framework. "It was really important to develop the handbook so that all the vocabulary would be the same across the district. And every single year, we're going to have to go over the foundations in language, and what we believe in with the staff. Our goal is to have 80% of the staff understand the foundation of what MTSS is," said Garton. "If you just jump into a school and start implementing all of this, it would not be successful; you have to lay the foundation. If you don't spend three years preparing for this, it's probably not going to happen the way you want it to," she added.

Blalock agreed, underscoring the importance of making sure all staff, including veteran educators, are on "the same page" with regard to the district's way of doing business:

And then you have to remember also that after you spend the three years preparing, if leadership changes, you have to start at zero, go back. That's something I'll take on personally. We had some veteran administrators come in and you automatically assume that if you have systems in place, the next man up should carry over. And the pandemic didn't help, but we've noticed that we have to do a little bit more to shore up their understanding of what North College Hill is about, what our vision is about, why we believe systems are important, how MTSS fits into all of our systems. And that's us taking a step back and saying, 'All right, we need to move a little slower to go faster.' And I think that's where we're at.

Going back to go forward. Like all districts, the pandemic took a toll on the speed with which the district was making progress in improving teaching and learning across all schools. "We were moving pretty strong and then COVID kind of smacked us in the face and we've had to do some recalibrating. With all the gains that we had made the first five years, I feel like I'm starting over, starting from scratch. We have the systems in place, but just the idea of making sure everybody's on the same page and whatnot - that's what keeps me up at night at this point," explained Blalock.

With a new team of administrators in place, NCH returned to the basics, which, according to Blalock, meant starting with the importance of systems and making sure everyone, at all levels, had a solid understanding of the OIP. "Everything starts with systems. We use the OIP process with fidelity in looking at data, using data, and managing the flow of data up, down, and across the board" he said.

"For me, as the chief instructional leader, it's about making sure the administrators are on the same page and moving in the same direction." And that begins with establishing trusting relationships at all levels and among levels of the system. "I personally believe everything starts with trust and building those relationships. And once you establish strong relationships, you can move forward. From central office, we have to work extremely hard, diligently, to have a level of trust from our administrators, and then also to the teachers, and I'll go back to that spiral up and spiral down. We have to trust the teachers and they have to trust us. And every now and then, just like in every family, we have some individuals who we have to redirect to make sure that they're on the same page. And we can't be bashful about that, we need to step right in and redirect when it's needed," said Blalock.

Sharing leadership, redefining coaching. As noted above, shared leadership through the use of aligned collaborative leadership teams (i.e., DLT-BLT-TBT/GLT) is a hallmark of the OIP-OLAC framework, which was developed to support each level of an education system in building the capacity of other levels of the system.

Garton believes that establishing trust involves empowering educators and teams to make decisions using the systems that have been put in place: "I have always expressed to teachers, and I think this is something we don't do enough, that it's actually the Building Leadership Team that basically runs the building. At the end of the day, of course, the administrator is in charge, but if that BLT is strong and has the responsibility to lead the building, it keeps the systems going."

Blalock and Garton recognize the importance of empowering educators to work together, recognizing that no one educator has all the knowledge and skill needed to meet the needs of every student. when working in isolation. "We changed our whole structure and thought process about instructional coaching. In the past, teachers that struggled were the only ones being coached. Now, coaching is seen as a process between the teacher and the coach; it's confidential and there's no evaluative component in it," said Garton.

According to Garton, this year, over 90% of NCH's teachers volunteered to be coached at some level. "They're willing to say to their coach, 'hey, I don't get this whole MTSS thing.' And we have coaches who can then say 'let me share with you how this could work for you.' I really believe it's one teacher at a time that sees the difference; instead of us just telling them, they see it and become someone who wants to try," she said.

Never done. District leadership continues to work on communication among levels — from the DLT to BLTs to GLTs, and from GLTs to BLTs to the DLT. "We're not perfect at it but we're going to get better," said Garton. Plans are underway for next year that involve the DLT, which Garton facilitates monthly, to use a dedicated dashboard for reviewing building-wide data across schools and identifying ways that central office administrators can support building leadership.

"We'll look at what help buildings need from the district and determine who's going to take the information back to the BLTs and then report back to the DLT at its next meeting," explained Garton. "We're never done!"

References

Barr, S. L. (2012). State education agencies: The critical role of SEAs in facilitating school district capacity to improve learning and achievement for students with disabilities. University of Minnesota National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrievable from http://www.movingyournumbers.org/images/resources/81554-sea- guide.pdf

Fullan, M. (February 2021). The right drivers for whole system sucess. Centre for Strategic Education CSE Leading Education Series #01, 1-44.

Fullan, M. (May 2011). Choosing the wrong drivers for whole system reform. Centre for Strategic Education Seminar Series Paper No. 204, 3-19.

McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. Guilford Press.

For More Information

For more information about North College Hill's (NCH) work to improve learning outcomes for all children, contact:

- Eugene Blalock, Jr., Superintendent, at blalock.e@nchcityschools.org or by phone at 513.931.8181 (ext. 14302).

- Michelle Garton, Director of Teaching and Learning, at Garton.M@nchcityschools.org or by phone at 513.931.8181.

See the NCH Journey 2021 video, which highlights the district's progress over the past few years:

For more information about Ohio's work to support the effective use of MTSS as part of the Ohio Improvement Process, contact Jo Hannah Ward, Director, Office for Exceptional Children, Ohio Department of Education, at johannah.ward@education.ohio.gov.

For more information about resources to support districts, contact OLAC Co-directors Dr. Jim Gay at jimgay@basa-ohio.org or Karel Oxley at Oxley@basa-ohio.org.