Believing in the Possibilities: Creating Open and Collaborative Cultures to Provide Equitable Learning Opportunities and Improve Learning for Each Child

“Every week we talk about creating a culture of respect, creating a culture of belief; the culture here is something that’s paramount that needs to be embraced and, in some cases, changed for our students to be successful,” said Dennis J. Dunham, Superintendent of the Leetonia Exempted Village (EV) School District in northeastern Columbiana county.

“It’s a lot of work to change and stem the tide of ‘I can’t believe’ to the tide of ‘we can do better here,’” added Dunham, a veteran educator now in his 41st year of serving as a teacher and administrator in northeastern Ohio. In August 2020, Dunham assumed the superintendency of Leetonia EV Schools, a small district serving about 550 children in kindergarten through twelfth grade. Kindergarten (K) through sixth-grade students attend Leetonia Elementary School, and grades 7 – 12 students attend Leetonia Junior/Senior High School. Both schools are housed in one K12 complex, something Dunham says provides “a natural fit for collaboration across all grade levels.”

About 25 miles north of Leetonia, Dr. Andy Tommelleo, Superintendent of Liberty Local Schools (Trumbull County), is also working with educators at all levels of the school system to change the culture of the district in ways that benefit each of its 1,250 students. Liberty Local serves children in three school buildings – a preschool through sixth-grade school, a junior high school, and a high school – and also provides services through the virtual Leopard Cyber Academy.

“Our mission -- and our commitment -- is to make sure that we are providing access and opportunities for all students,” said Tommelleo. “When you look through the lens of equity, you start looking at everything you do in terms of how you’re giving access to your students. You consider whether you’re being cognizant of student cultures and practices; you look at your materials and how instruction has been provided to students, and whether it’s impacting students positively or negatively. It’s a mindset,” explained Liberty High School Principal Akesha Joseph.

Believing in the possibilities of higher levels of learning and achievement for all students is at the heart of what both districts are doing to change mindset and practice at the classroom, school, and district level.

The Four Domains of Inclusive Instructional Leadership

Changing mindset and practice is a key function of leadership. Inclusive instructional leadership – leadership that is grounded in a commitment to equity and intended to engage all adults in working together to improve learning opportunities and outcomes for all students – depends on practices in four inter-related domains of action: (1) prioritizing the improvement of teaching and learning, (2) building capacity through support and accountability, (3) sustaining an open and collaborative culture, and (4) promoting system-wide learning.

These four domains, which can be characterized as non-negotiable areas of district leadership practice required for continuous district-wide improvement on behalf of all students, are described in a literature review conducted at the request of the University of Cincinnati Systems Development & Improvement Center in 2021 by Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) scholar, Dr. Stephen Anderson, and Dr. Santiago Rincon-Gallardo, Chief Research Officer for Michael Fullan Enterprises.

Districts can use the Systemic Improvement Practices Review (SIPR), a web-based assessment instrument, to identify their relative strengths and weaknesses across the four inclusive leadership domains. Members of the district leadership team (DLT) complete the SIPR;, responses from individual DLT members are then aggregated, and district-level ratings are obtained. DLTs can use the instrument and the associated discussion guide to monitor their progress, reassessing periodically (e.g., annually) in relation to the implementation of agreed-on strategies and actions to reach identified focused goals.

Evolution of the SIPR

The Moving Your Numbers initiative was undertaken in 2011-2013 under the auspices of the National Center on Educational Outcomes to identify districts that were improving learning outcomes for all groups of children, particularly those identified as children with disabilities, as part of district-wide continuous improvement efforts. The Moving Your Numbers (MYN) District Self-assessment guide (Telfer & Glasgow, 2012), one of many products developed over the two-year MYN study, provided a tool for district and school teams to use in considering their level and scale of implementation of practices associated with inclusive leadership. However, the tool was not a validated instrument.

Later, in 2017, a two-phase validation study was conducted by the University of Cincinnati Evaluation Services Center and WordFarmers Associates (Howley, 2017; Maltbie, Morrison, Duan, & Dariotis, 2017) to establish both content and construct validity.

The resulting Systemic Improvement Practices Review (SIPR) assessment instrument and associated discussion guide provide districts with an easy to use, reliable, and valid way to identify their current level of implementation of four domains inclusive instructional practices, and areas that need to be strengthened.

“We used the SIPR to see exactly the needs of our district. We completed it collectively as a DLT and from the results we identified culture as our first area of need. The other area was prioritizing teaching and learning,” recalled Jackie Dunnigan, Principal of Leetonia Elementary School.

“The area that really jumps out to me is open and collaborative culture,” said Leetonia Jr/Sr. High School Principal Troy Radinsky. “We were in a situation that was somewhat suppressed having been given boundaries as to what we could or could not do in practice so one of the greatest things to come from the SIPR was having open and collaborative conversation,” he added.

Asking the right question: What are the adults doing? Dunnigan and Radinsky agree that a focus on adult implementation is critical in changing the trajectory for students and what they can achieve. “We cannot change our students. We just can’t. So, we have to change what we’re doing in the classroom to make our students more successful. We’ve been having some really, really tough conversations,” explained Dunnigan.

Shifting the focus to what the adults do was characterized by Dunnigan as a “huge aha moment” for staff last spring. “They’re like, wow, we never said, ‘what can we do?’ We only said, ‘what can kids do?’”

Like Dunham, Tommelleo is also in his second year of serving as superintendent of his current district. A longtime educator, he was a superintendent in Pennsylvania, a counselor, a teacher, and a consultant with State Support Team (SST) Region 5, which is based at the Educational Service Center (ESC) of Eastern Ohio and is one of 16 SSTs in Ohio.

In describing the benefits of SIPR use, Tommelleo said, “for me, it was the questions that are embedded in it and asking the right questions, which are sometimes hard to identify. Asking the right questions leads to more in-depth conversation, more in-depth analysis needed to identify priorities and align the work, and a foundation for coaching personnel. We now have a lot of arrows moving in the same direction. We’re transforming the system with a different lens focused on changing mindsets, belief systems, and how adults do what they do every day.”

Liberty Local Curriculum Director Pamela McCurdy, who has served 22 of her 25 years as an educator in Liberty, believes using the SIPR has caused the staff to be more reflective in looking at adult practice. “We’ve seen many times we can’t change students, so we changed the adults. We have to make sure we’re continuing to align the work, have those difficult conversations and, as Dr. T. says, ‘dive in and coach!’”

Sustaining an Open and Collaborative Culture

Sustaining an open and collaborative culture – one of the four inclusive instructional leadership domains of action, involves developing structures, routines, and skills for effective collaboration across all levels of the school system; maintaining two-way communication between all levels to improve the quality and equity of teaching and learning; and sharing leadership authority, practice, and influence within central office and between district and school leaders.

OIP as the organizing framework. The Ohio Improvement Process (OIP) is a five-step improvement cycle that is operationalized through the establishment and use of aligned collaborative leadership teams (i.e., DLT-BLT-TBT) at the district, school, and classroom levels.

Using the “nested” OIP team structure, as described in Ohio’s Leadership Development Framework (2013) fosters alignment of work aimed at meeting district-identified priorities, and coherence in the use of focused strategies and actions for improving teaching and learning on behalf of all learners and groups of learners across all levels of the school system. The OIP team structure also provides a forum for job-embedded professional learning, shared leadership, and building the capacity of all personnel to improve performance and equity.

“We’re a small district but we try to make sure all voices are heard within this district and beyond in getting all stakeholders involved,” said McCurdy. “We’re always focusing on the students first; and to make it inclusive for the students, we need to make it inclusive for the adults as well,” she said.

Liberty Local’s 25-member DLT holds quarterly full-day meetings involving all administrators, teachers from across grade levels and content areas in the district, additional personnel such as the school psychologist and literacy coach, and a parent representative. Each school’s BLT – with representation from every grade level and content area – meet monthly and DLT members from particular schools serve on their school’s BLT to support two-way district-to-school and school-to-district communication. TBTs meet according to each school’s established schedule.

Districts like Liberty and Leetonia are using the SIPR and OIP team structures to consider how their beliefs and practices have included or excluded some groups of children and are taking steps to make the mantra “all means all” a reality.

For example, in Liberty, central office leadership personnel are working alongside building principals to make sure each child has needed supports. “Some children need more whether it’s more enrichment or more intervention supports. The shift that is needed and that we’re encouraging is for all adults to say it’s all kids. It isn’t just kids with disabilities, or kids identified in a subgroup that get intervention. Supporting children crosses the board and it’s all hands on deck,” offered Jessica Kohler, special education supervisor and former principal in the district. “Every person, every role, is important when you’re talking about instructional leadership; everyone has a significance in it,” stated Joseph.

In Leetonia, as in Liberty, district and school leaders are working hard to change the culture to be one of “great and even higher” expectations. Radinsky explains: “We’ve been battling the thought that mediocrity was okay. And we’re going to great lengths to provide opportunities for kids now that they haven’t had before and build upon the belief system that they are capable of doing great things and can achieve more,” he said.

Dunnigan credits the use of OIP team structures to foster open and collaborative conversation – along with superintendent leadership in allowing that collaboration to take place – with changing the beliefs and practices in Leetonia. “I think it was truthfully this (OIP) process; it was the aha moment of having TBT members change from saying ‘these are your kids’ to ‘wow, no, these are my kids and what do I need to do to meet their needs.”

“The DLT-BLT-TBT structure has enabled us to enrich our staff with PD and opportunities they need to be successful, enable us to see the needs of our district as leaders, and actually to empower our teachers to be leaders. The collaboration was huge because we didn’t have the opportunity to collaborate grade to grade, and grade level to grade level, so that’s a huge piece to the conversations that are happening between grade levels that never happened before,” said Dunnigan.

Leetonia’s DLT meets every month to two months with representation from classified and certified employees and residents. Radinsky and Dunnigan selected individuals to be invited to participate as DLT members, which include central office leadership, principals, teachers, intervention specialists, the literacy coach, a bus driver, and at times representation from State Support Team Region 5 and/or the Educational Service Center. BLTs meet monthly, and TBTs meet monthly in addition to members participating in before- and after-school PD aligned with TBT priorities.

“Troy and I used to do all the speaking in BLT meetings. Now our teachers are taking on that leadership role, and they’re running our TBTs. To have that collaboration is huge. Now all of our teachers come to the TBT – our Title teachers, our intervention specialists, our speech-language pathologist, our literacy coach – basically anyone in this building teaching or having something to do with providing instruction to children,” explained Dunnigan. “Our TBTs are taking shape to support those departments working together; it’s just another effort to grow across the board,” added Dunham.

Improving core instruction for ALL. In both Leetonia and Liberty, “growing across the board” and fostering systemwide learning through the use of OIP team structures is focused first and foremost on making strong core (aka Tier 1) instruction accessible to every student. “Our priority is to create and provide strong Tier 1 instruction to all students. We can never be satisfied with where we’re at. All the work we’ve done at the district and school level has to get down to the classroom along with professional development and peer support,” said Kohler.

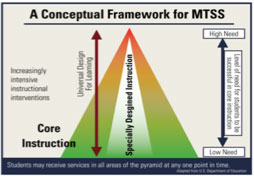

Like Leetonia, Liberty Local uses a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) model to design and deliver core (Tier 1) instruction and universal supports to all children, plus any additional targeted (Tier 2) and intensive (Tier 3) supports a student may need. At Liberty High School, a period was added to the schedule for the purpose of providing additional targeted supports to students who are not on track academically, as well as to students who are advanced academically. “The additional period allows students who need additional support to go to the targeted English language arts room, to the targeted math room, or to another room that provide resources and time for enrichment. The biggest thing is trying to see where our kids are and using benchmark and diagnostic assessment data to get the right support to individual students,” offered Joseph.

“MTSS to me really is pinpointing what students need, personalizing their learning, and using the right tools and the right resources to meet their needs,” explained Kohler. “It helps us structure students’ day; everyone gets tier 1 instruction and the scaffolds and supports as needed,” added McCurdy.

“Our primary focus is to improve and allow academic achievement and success so that it’s natural here. Prior to me arriving, the district had quite a bit of turnover in some of the leadership positions with two temporary superintendents in a six to seven-month period. Academics was sometimes on the back burner because of all the other issues that were on the front burner and our staff was turned upside down in some cases; now they’re right side up and can focus on student achievement,” said Dunham.

Inclusive instructional leadership is leadership that keeps the instructional core at the center of the district's work, uses focused goals and strategies and engages all adults across the system to build system-wide capacity, attends to equity across all aspects of the district operation, and uses inquiry processes and evidence to inform decision-making. Inclusive instructional leadership practices - leader practices that are grounded in a commitment to equity.

In keeping with their focus on changing culture, Leetonia has used a tiered model to provide positive behavioral supports and interventions (PBIS) in both schools. Coupled with their efforts to improve academics, Dunnigan and Radinsky are seeing positive changes happening across the district: receiving a Bronze Award from the state for their PBIS work, seeing significantly increased participation in a before- and after-school program that incorporates STEM activities and instructional strategies, seeing staff welcome opportunities to engage in self-reflection and accept critique, making PD more sustainable and meaningful, and seeing teachers share responsibility for improving the learning of all students.

For example, at the junior/senior high school level, intervention specialists are assigned to grades 7-12 content area teams so they can become more effective in supporting student learning in various content areas. “It creates a new dynamic of communication and collaboration between staff members, and it will continue to grow. I’m excited to see the progress we’ve already made,” said Radinsky.

Leading for Equity

Ensuring equitable opportunities to learn and improving teaching and learning for each child, regardless of classroom or school assignment, means that all educators, at all levels of the system, are working together to meet the needs of all children. McCurdy describes herself and her colleagues as lead learners: “we’re all part of this process; we’re all embedded in the process…inclusive leadership means that you’re side-by-side.”

Support is provided to Liberty, Leetonia, and other districts in Columbiana, Mahoning, Trumbull, and Ashtabula counties by SST Region 5 and area ESCs. Leetonia and Liberty are particularly appreciative of the support in using evidence-based literacy practices and PBIS, and in strengthening family engagement, and the trusting relationships regional providers have built with teachers and other educators in the districts. “We’re fortunate to have a lot of lifelines,” offered Radinsky.

Both districts also recognize that job-embedded, sustainable professional learning is naturally fostered through the use of TBTs. “TBT conversations enable our teachers to add to their toolbox. Not only are they discussing data and changing instruction, but they’re also learning one more strategy to use; we try to emphasize the PD every step of the way,” said Radinsky. Dunnigan added, “our TBTs pretty much run as PD with an additional PD before and after school.”

Support is also available from the Ohio Leadership Advisory Council (OLAC), which offers a wealth of online learning resources to support the use of inclusive instructional leadership practices by district and school leaders, DLTs, BLTs, and TBTs; and from the Ohio Leadership for Inclusion, Implementation, and Instructional Improvement (OLi4) project, which supports principals in using inclusive instructional practices to support teacher learning and the effective use of BLTs and TBTs.

Two Liberty Local principals are participating in the OLi4 program this year, which involves a two-year commitment and engagement in centralized professional learning, regional cadre meetings to support application of knowledge gained, and in-school coaching. “We’re looking to have the second cohort of our principals participate in OLi4 next year,” said Tommelleo.

Opportunities are expanding for all children in Liberty and Leetonia. For example, in Liberty High School, increased numbers of BIPOC students are participating in advanced courses and college credit plus programs. “Instructional leadership is not just about one population; it’s about all populations,” said Joseph.

“We’re not going to create a culture of respect and belief or work on trust and relationship issues every now and then. There’s not a day off; it has to be every moment,” said Dunham.

Resources

Anderson, S. E., & Rincón-Gallardo, S. (2021). Learning to lead school districts effectively: A review of the literature. University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Each child means each child: Ohio’s plan to improve learning experiences and outcomes for students with disabilities. (2021). Ohio Department of Education, Office for Exceptional Children. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Special-Education/Improving-Educational-Experiences-and-Outcomes/EachChildMeansEachChild.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US.

Howley, A. (2017). Moving Your Numbers (MYN): Instrument validation study phase 2 report. WordFarmers Associates.

Maltbie, C., Morrison, A., Duan, Q., & Dariotis, J. (2017). Evaluating the evidence base for using the Moving Your Numbers (MYN) district self-assessment guide for technical assistance: Key results from phase 1. Evaluation Services Center, University of Cincinnati.

Telfer, D. M., & Glasgow, A. (2012). District self-assessment guide for moving our numbers: Using assessment and accountability to increase performance for students with disabilities as part of district-wide improvement. University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.movingyournumbers.org/images/resources/81157-self-assessment.pdf.

For More Information

For more information about the districts featured in this issue of Cornerstone Connections and how they’re using inclusive instructional leadership practice to provide equitable opportunities to learn for each child, contact:

Dennis J. Dunham, Superintendent, Leetonia Exempted Village Schools, at 330.427.6594 or via email at ddunham@leetonia.k12.oh.us.

Andrew Tommelleo, PhD, Superintendent, Liberty Local Schools, at 330.759.0807 or via email at andy.tommelleo@liberty.k12.oh.us.

For more information about OLi4, contact Robert White, PhD, Research Associate, or Katie Dean, Junior Research Associate, University of Cincinnati, Systems Development & Improvement Center, at white3rm@ucmail.uc.edu and deank9@ucmail.uc.edu.

For more information about resources to support districts, contact Dr. Jim Gay, OLAC Co-director, at jimgay@basa-ohio.org; or Karel Oxley, OLAC Co-director, at Oxley@basa-ohio.org.