Passion and Purpose: Ohio's Investment in Literacy Advances State's Commitment to Equity, Improved Outcomes for Every Child

An accumulating body of research shows how important state education agencies (SEAs) are in supporting a new model of accountability – one that is grounded in a commitment to continuous improvement and designed to build capacity at each level of the system in order to improve outcomes for every student, teacher, administrator, and local community. In Ohio, Each Child, Our Future (Ohio’s Strategic Plan for Education 2018-2024) places equity at the center of accountability based on this model.

Nowhere is the commitment to improve equitable opportunities to learn more apparent than in the state’s work to improve language and literacy on behalf of all students. Improved language and literacy, in fact, leads to improved educational outcomes across the entire education system.

According to Dr. Melissa Weber-Mayrer (pictured above), who is leading Ohio’s literacy improvement efforts, “Our work is about building a stronger system to support the adults so that we can increase language and literacy skills for all of our learners in all of our schools in all of our regions of the state. We’ve been able to increase teacher knowledge of the foundational skills of reading, but in order to benefit all children, that knowledge has to be transferred into practice that is supported on an ongoing basis through the statewide system.”

Investing in Preparing Every Child to Read Well

The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) has put literacy education front and center. Through various coordinated initiatives, the Department has invested heavily in the improvement of language and literacy instruction. These initiatives support a common mission: ensuring that all school districts effectively teach all children to read.

As emphasized in Each Child, Our Future, the improvement of literacy outcomes is essential for improving opportunities for every child to develop foundational knowledge and skills, access content across academic areas, and transition to meaningful post-secondary endeavors upon graduation.

Ohio’s literacy investment is supported through a variety of federal and state-supported efforts including:

- Ohio’s State Systemic Improvement Plan (SSIP), required by the United States Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (USDoE, OSEP) under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA), focuses on improving early (PreK-grade 3) language and literacy skills through enhancing the state’s regional infrastructure to support language and literacy improvement and the implementation of a statewide Early Literacy Pilot. The state has invested in at least one Regional Early Literacy Specialist in each of the state’s 16 regions who provide intensive supports throughout their region for language and literacy improvement. The Early Literacy Pilot involves providing intensive support to 15 districts with varying demographics (i.e., rural, suburban, urban, high-poverty, etc.) focused on developing and enhancing the shared leadership structures of the Ohio Improvement Process, a multi-tiered system of supports, family and community engagement, and building teacher capacity to implement a scientific approach to teaching reading.

- Ohio’s Striving Readers Comprehensive Literacy Grant, awarded to ODE in 2017 from USDoE, bolsters the use of evidence-based language and literacy instruction within the classroom, birth through grade 12, in multiple districts across the state (i.e., 46 subgrants, including 21 consortium awards involving about 112 districts).

- Ohio’s State Personnel Development Grant (SPDG), awarded to ODE from USDoE, OSEP, focuses on building the capacity of the state system (from the state to regions to districts to schools to classrooms) to support language and literacy development through intensive work with districts across the state, and with institutions of higher education to foster the development of university-district partnership efforts designed to support teacher education candidates and teachers to more effectively teach all children, including struggling readers, to read.

- Ohio’s What Matters Now (WMN) Coalition, funded through Learning Forward1 as part of a three-state national initiative, focuses on the use of improvement science processes (e.g., PDSA cycles) and high-quality instructional materials to support teacher-based teams, schools, and districts in improving early language and literacy for all children. See Case in Point descriptions of partner districts involved in this work, beginning on page 5.

- Ohio’s Third-grade Reading Guarantee, a statewide policy to identify and support children, Kindergarten – grade 3, who may be at risk for reading failure. In support of this policy, legislation requires districts with a D or F report card designation in K-3 literacy for two consecutive years and fewer than 60% of students achieving proficiency to submit reading achievement plans, providing an opportunity for them to receive feedback and support to improve reading instruction for all children.

Ohio’s Plan to Raise Literacy Achievement, released in 2018, serves as a guidepost for the implementation of literacy improvement work through the multiple efforts and funding sources such as those listed above. The plan outlines the state’s theory of action with regard to literacy instruction and is meant to serve as a “cohesive state literacy framework aimed at promoting proficiency in reading, writing, and oral language for all learners” (p. 5).

“Ohio’s plan is a living document; each year, we bring together a state literacy team comprised of stakeholders from across the state with expertise in emergent literacy, early literacy, conventional literacy, and adolescent literacy to help us identify and address gaps and continually improve upon the original plan and highlight evidence-based practices,” explained Weber-Mayrer.

Not a One-Size-Fits-All Approach

Ohio’s approach to improving literacy recognizes the importance of word recognition through decoding and language comprehension (i.e., the Simple View of Reading). These building blocks support the development of other conventional literacy skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, spelling, and writing.

Another way to think about the Simple View of Reading is in terms of foundational skills, often referred to as the “five components of reading.” These components are phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Most often addressed in kindergarten through fifth grade, Ohio recognizes that these skills are critical not only for struggling readers but for all readers across all grade levels.

Ohio has actively avoided involvement in what are euphemistically called “the reading wars.” Instead, it focuses on the use of data and tiered supports to identify evidence-based strategies for supporting all students, including those identified as students with disabilities, those who are English learners, and those identified as gifted and talented. Weber-Mayrer explains:

There are certain ways of teaching reading that work for some children, or groups of children, and maybe not others. Our work is to fill the gap for the children for whom our way of teaching reading might not be the most effective. It’s really about opening the way, opening our minds as adults to how we think about and learn about and talk about teaching reading, and how children learn to read, because there are lots of different ways. I’ve been asked on multiple occasions, ‘what does all learners mean?’ ‘All learners’ means all of our learners; it means having high expectations for all children, including our children with disabilities, including our English learners, including all of our sub-categories of students. Therefore, we know that it’s not an either/or; there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. We look at what the research tells us – what was done for what population of students, what was the outcome, and how might students in Ohio benefit from those evidence-based strategies.

Structures to Support Scale and Sustainability

Improving literacy for every learner requires a systems approach, and building a stronger system requires attention to all levels of the system – an approach known as “systems thinking.” Attending to one level of the system (e.g., a school) in isolation isn’t sufficient to achieve the kind of scale necessary to sustain the use of improved literacy practices on a statewide basis.

Systems thinking focuses on critical connections across parts of the system as well as on cycles of cause and effect. According to Barr (2012, p. 1), it is based on the belief that the component parts of a system can best be understood within the context of their relationships with each other and with other systems, rather than in isolation…. [and it also] focuses on cyclical, rather than linear cause and effect, relationships.

Weber-Mayrer and her ODE colleagues recognize the need to address all parts of the educational system in order to extend work being done with and through partner districts. This work needs to influence all other districts in the state by demonstrating the applicability of lessons learned to all districts and infusing those lessons into the ongoing efforts of the regional statewide system of support (SSoS) using Ohio’s improvement framework – the Ohio Improvement Process (OIP).

A System Approach: What's Different

- Go beyond integration to unification

- Redesign work at all levels to be about improving capacity at other levels (coherence)

- Redefine scale by designing state-developed products and tools for universal access and applicability

- Ensure intentional use by all regional providers of a consistent process and connected set of tools

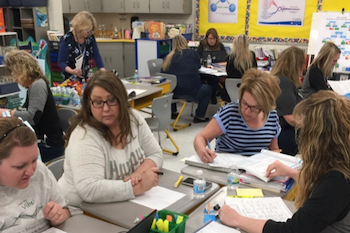

Fostering shared responsibility through common understanding. To that end, a regional literacy network was established to build capacity of regional providers [i.e., state support team (SST) and educational service center (ESC) providers]. About 90 regional personnel from all parts of the state meet monthly for one to two days to build their collective knowledge and know-how in language and literacy instruction across the grade bands.

Additionally, 17 regional early literacy specialists (RELS) across all 16 SSTs, as well as district literacy coaches, are supported through the State Systemic Improvement Plan to work intensively with districts in each region of the state; and two adolescent literacy specialists are being supported through the Striving Readers grant.

“The goal of the regional literacy network is to build a common language and message, and shared understanding across our SST and ESC providers because they’re the ones who are providing that direct, targeted, and intensive support to districts,” said Weber-Mayrer. “Common understanding is key to ensuring that evidence-based literacy practices are implemented with fidelity,” she added.

The use of common system-level assessments and protocols (e.g., the reading tiered fidelity inventory) and Ohio’s Plan to Raise Literacy Achievement offer additional support for regional providers and district and school personnel. “Districts don’t have a lot of time to sift through a lot of information; their job is to teach children. One of our goals is to build model sites around the state so we can point districts to other similar districts when they have questions about evidence-based instruction,” explained Weber-Mayrer.

Breaking down silos to increase coherence and shared learning. Moving beyond silos – for example, between general education and special education personnel, between higher education and district personnel, and between teachers and administrators – is necessary in order to maximize the collective expertise of these educators. Sharing and building expertise across the levels of the system – from early childhood through higher education – is critical for the improvement of literacy outcomes.

Weber-Mayrer reported that even though teacher understanding of the foundational skills of reading in pilot schools increased, on average, about 30% from pre- to post-tests, attending only to change at the classroom level is not enough. “We’ve learned that other important factors, like district and school leadership, and the use of high-quality instructional materials, are critical to extend the use of evidence-based literacy practices across classrooms and schools within a district,” she added.

“It’s vital to build principal knowledge so that when they conduct walk-throughs at various grade levels, they can recognize evidence-based language and literacy instruction when they see it, ask probing questions, and address resource gaps identified by TBTs and BLTs. Feedback from principals suggests they feel more effective when they have even a little bit of knowledge,” said Weber-Mayrer.

“We’ve also learned that we need to be very thoughtful in including all educators in the work so that general educators, intervention specialists, paraprofessionals, and related services providers like speech-language pathologists can learn together and from each other. More children are benefitting from the knowledge of educators when those educators are working together,” stated Weber-Mayrer.

Cultivating more meaningful university-district partnerships that focus on preparing all teachers’ use of effective practices to teach all children to read is another “silo busting” endeavor. This effort is supported through Ohio’s SPDG. Rather than blame anyone (e.g., higher education for not adequately preparing teachers or districts for not adequately coaching teachers), a Higher Education Literacy Steering Committee is working to promote improvement broadly across higher education and PK-12 institutions. Its aim is to develop products (e.g., sample syllabi) that higher education institutions can use to strengthen their 12-hour reading core courses, and establish a community of practice through which higher education and district partners can learn together and from one another. Listening to each other’s perspectives and engaging in shared learning are critical for strong and lasting university-district partnership focused on improving student outcomes (Curcio & Ascetta, 2019).

Central to the work is the focus on differentiating instruction to meet learner needs. “We’re trying to support preservice candidates and practicing teachers to both prevent a student from becoming a struggling reader through high-quality, differentiated core instruction and to identify when a child is struggling to read, pinpoint the root cause of that struggle, and identify and use evidence-based practices to address those needs,” said Weber-Mayrer.

Case in Point: Highlights from Partner Schools

Sponsored by Learning Forward with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, What Matters Now (WMN) involves states in a three-year effort to apply improvement science methods within a Networked Improvement Community that includes the Ohio Coalition, along with state coalitions in Maryland and Rhode Island. While each state has its unique focus (e.g., science of reading), all three states are working to improve the use of high-quality instructional materials to improve educator practice and student outcomes.

The Ohio WMN Coalition involves state and regional leaders, and representatives from four schools in three partner districts: Schreiber Reading & Math Preparatory School (Canton City), Medill and Tallmadge elementary schools (Lancaster City), and Western Primary School (Western Local). The University of Cincinnati Systems Development & Improvement Center, working in collaboration with WordFarmers Associates, serves as the collaborative partner for the Coalition.

Highlights from each partner school follow:

Schreiber Reading & Math Preparatory School. One of seven PreK-grade 2 buildings in the Canton City School District, Schreiber serves approximately 300 students, all of whom receive free or reduced-price lunches. More than half of the students, according to Principal Aaron Bouie III, need intensive intervention in literacy, in addition to high-quality and differentiated core instruction, to reach the district’s goal of ensuring that every child attains at least one full academic year of growth each year.

“My personal goals for Schreiber are to build the capacity of our teachers so that they understand the scientific-based approach to the teaching of reading, and build a system that supports teachers in collaborating, providing interventions when needed, and monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the instruction and interventions we provide,” explained Bouie.

Schreiber participates in Ohio’s Early Literacy Pilot, supported through the SSIP. It receives support from in-district literacy coach Melissa Butler (pictured with Bouie above) and a Regional Early Literacy Specialist. All Schreiber teachers received intensive professional learning in literacy using Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS)2, and Principal Bouie is participating in Ohio’s SPDG. “I remember two years ago when we started the work as a district, our lack of strong core instruction was a hard pill to swallow. Now, when we look at our data, we can say that even though we’re still not where we need to be, every single one of our students improved because of very specific intervention tied directly to their needs,” reflected Bouie.

Bouie gives credit to literacy work for Schreiber’s improvement in the school’s use of OIP structures (e.g., teacher-based teams, building leadership teams) and his own growth as an instructional leader. “Our TBT conversations are becoming more natural and fluid, evolving from a checks and balances compliance focus to one that is about improving instruction and student learning.” Participation in WMN, according to Bouie, “supports the use of a collaborative approach focused on continual growth and improvement for every child across the board.”

“All of the work we’ve embarked on – using the OIP, participating in LETRS, SPDG, and What Matters Now – is about making sure that no matter who you are, what your background is, what your challenges are, or what your needs are, that you will be provided an opportunity to learn, and access to the information that can change your life or allow you to reach your dreams or goals or aspirations through high-quality professionals who are dedicated to their craft and direct their practices to ensure that they are equitable, that everyone has what they need to learn, not that everyone gets the same thing. Equity screams and champions the work that we’re doing across the board,” said Bouie.

Medill and Tallmadge Elementary Schools. Medill and Tallmadge elementary schools in the Lancaster City School District serve about 682 and 575 students, respectively, in grades K-5 in what principals describe as an increasingly diverse community. Both schools are involved in the Early Literacy Pilot, receiving LETRS professional learning and in-district coaching from Leigh Johnson, and both are committed to improving literacy outcomes for every child.

“Our mission is to make sure every student that comes through our building is a better reader than they were before they came,” said Jennifer Woods, Principal of Medill Elementary School. Jake Campbell, Principal of Tallmadge Elementary School, agrees, noting “everybody moves and everybody gets from point A to point B. It’s not about whether or not to identify a child; it’s about identifying and putting into place the right interventions to address reading deficits. We want to make sure we know every single student and what their needs are,” he explained.

Both principals credit their schools’ involvement in the Early Literacy Pilot for their development of a shared understanding of evidence-based literacy practices.

“We’re better prepared to look at our three to five-year plan because we have better knowledge and better resources and better data to have those conversations. Our staff now has a common language, a more unified language, so when we say we want every child to be reading by third grade, we all know what that means and what’s involved from kindergarten all the way through. Having the opportunity to train all of our K-3 teachers, intervention specialists, and speech-language pathologists, and having job-embedded coaching, has given us a scope and sequence, allowed us to make good decisions about literacy instruction, and strengthened our TBTs,” said Woods.

“It’s powerful as a principal when you have a common language and can talk with teachers about what you’re seeing or not seeing. I want staff to feel that a walkthrough or observation from me is a coaching, not an evaluative, measure,” said Campbell.

Johnson, who previously served as Title I teacher providing intervention for struggling readers, recalls teachers saying, “‘Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it.’ They didn’t feel they had the expertise to address reading deficits in the classroom. Now teachers have more knowledge and are more confident in using evidence-based literacy strategies on their own. When I walk into TBTs, our people are looking at data and having some really good conversations,” Johnson said.

Woods, Johnson, and Campbell – pictured above from left to right with Dr. Jeromey Sheets, the district’s Director of Elementary Education – agree that their involvement in the WMN network has provided tools and support for refining TBT processes and extending professional learning.

“As a literacy coach, I use the Application of Concepts (AoC)3 tool as a coaching tool with teachers; it provides a way for us to look at strategies to improve their instruction,” said Johnson. “Using rapid cycle assessment is a whole kind of new ballgame for us,” observed Woods. Campbell agrees, adding “the collaboration with other districts has been a major benefit; it’s wonderful to hear another principal from another district and learn about their struggles, how they’re attacking them, and improving.”

Campbell and Woods also credit their involvement in the Ohio Leadership for Inclusion, Implementation, and Instructional Improvement (OLi4) project – a statewide principal development program developed and coordinated by the UC Systems Development and Improvement Center – for positioning them as fairly new principals to lead teacher learning more effectively and improve TBT and BLT functioning. “We were better able to give guidance to our staff as to what TBTs should look like, what team discussion should look like, and how frequently we needed to have them,” said Woods. “It was powerful because it set the tone and having quality TBTs was a definite high yield,” added Campbell.

“Our whole impression of the State Department has changed because of their drive for literacy. We’re being inundated with greatness from the state,” said Woods. Campbell added: “Our involvement in these initiatives has been very systematic and aligned and has made us stronger. I can tell you that right now, we are stronger.”

Western Primary School. Located in rural Pike County, Western Primary serves K through grade 3 students with varying needs. According to Principal Heather Thompson, the vast majority of residents are economically disadvantaged and students have limited opportunities and limited exposure to language and support systems. “We hope that by improving literacy skills, we’ll break that cycle,” said Thompson.

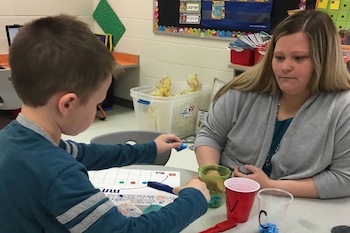

As part of the Early Literacy Pilot, teachers at Western participated in intensive LETRS professional learning. They have also received support from their Regional Early Literacy Specialist, and from K-3 literacy specialist and coach, Kim Montavon. These efforts have helped the school build capacity to provide high-quality literacy instruction.

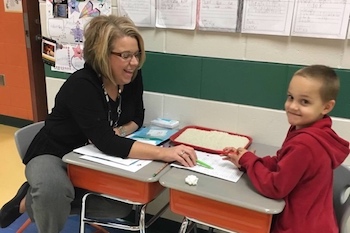

“Having these supports, especially in a small district where the principal is usually responsible for all PD, providing feedback, observations, and coaching, has been tremendously helpful. Being able to train all teachers and have everyone participate in the same training so we can talk the same language, has been critical,” explained Thompson (pictured with Montavon to the right).

Western Primary’s third grade state assessment scores improved by 13 percentage points and Thompson’s goal is to increase scores by at least 10% each year. During the 2017-18 school year, 51% of Western’s students met third-grade guarantee requirements; at the end of the 2018-19 school year, that percentage rose to 88%.

“Opportunities to be involved in the Early Literacy Pilot and other literacy work has impacted relationships,” said Thompson. “Our special programs coordinator has commented that he’s gained new knowledge in the science of reading, and our superintendent reported that our involvement has given the district renewed hope. Our coach has been an integral part of the work, developing relationships with staff and our RELS, and guiding our conversations, and I’ve learned alongside staff and now know what to look for and how to provide better feedback to teachers,” explained Thompson. “We are all one when it comes to this project and this pilot,” she added.

Western’s involvement has also strengthened its use of OIP structures and supports, reducing isolated practice and allowing teachers to focus on improving strong core instruction for all children.

“Our conversations have changed at the TBT level and my involvement in the WMN network has affected my practice in that it continually puts my thinking forward to continually learn no matter how long I’ve been in education,” said Thompson. “The recent focus on high-quality materials4 has changed our conversation in TBTs. Before we tried various materials, we found and didn’t necessarily pay attention to what was evidence-based or high quality. Now, we’re asking ourselves, ‘will this make a difference in student learning?’ and having that conversation in conjunction with continual professional learning.”

Thompson also praised the resources available on the Ohio Leadership Advisory Council (OLAC) site, as well as her involvement in OLi4, for helping her become a more effective instructional leader. “Being the principal is like working in an emergency room. You never know what you’re going to get when you walk in. The principal needs to be the person who says ‘this is what we need to do, this is the way, and this is where we’re going,’” she said.

Like Bouie, Thompson believes that investing in literacy is critical in advancing equity across the state. “We’ve always been committed to improving outcomes for all students, but the support we’ve received from the state has really helped us look at instructional practices and what works. The state’s recognition of the importance of literacy has helped us,” she said.

Annotations

1 For more information about Learning Forward and how it supports educators in leading and sustaining effective professional learning, go to: https://learningforward.org/.

2 Developed by Louisa C. Moats and Carol A. Tolman, LETRS is professional development that supports the delivery of comprehensive, integrated, language and literacy instruction.

3 The LETRS Application of Concepts tool is a Voyager Sopris Learning, Inc. product.

4 For more information on why instructional materials matter, go to: https://learningforward.org/journal/december-2018-volume-39-no-6/materials/.

References

Barr, S.L. (2012). State education agencies: The critical role of SEAs in facilitating school district capacity to improve learning and achievement for students with disabilities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrievable from http://www.movingyournumbers.org/images/resources/81554-sea-guide.pdf.

Curcio, R., & Ascetta, K. (2019). A bridge between teacher education and school: Professional development school district sets goals for an entire district. The Learning Professional, 40(3), 30-34.

Ohio Department of Education. (2019). Each child, our future. Ohio’s strategic plan for education (2010-2024). Columbus, OH: Author.

Moats, L. C. (1999). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers. Retrievable from http://www.louisamoats.com/Assets/Reading.is.Rocket.Science.pdf.

Ohio Department of Education. (2018). Ohio’s plan to raise literacy achievement: Birth through grade 12. Columbus, OH: Author. Retrievable from http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Literacy/Ohios-Plan-to-Raise-Literacy-Achievement.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US.

Ohio’s leadership development framework (2nd ed.). (2013). Columbus, OH: Buckeye Association of School Administrators (BASA). Retrievable from https://ohioleadership.org/storage/ocali-ims-sites/ocali-ims-olac/documents/OLAC_LDF.pdf

Steiner, D. (2018). Materials matter: Instructional materials + professional learning = student achievement. The Learning Professional, 39(6). Retrievable from https://learningforward.org/journal/december-2018-volume-39-no-6/materials/.

Weber-Mayrer, M., Piasta, S. B., Ottley, J. R., & O’Connell, A. A. (2018). Early childhood literacy coaching: An examination of coaching intensity and changes in educators' literacy knowledge and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 14-24.

For More Information

For more information about Ohio’s literacy initiatives, contact Melissa M. Weber-Mayrer, PhD, Director, Office of Approaches to Teaching and Professional Learning, Ohio Department of Education, at 614.728.8095 or via email at: Melissa.Weber-Mayrer@education.ohio.gov.

For more information about Ohio’s SPDG, contact Ashley K. Hall, PhD, Education Program Specialist & SPDG Project Director, Office for Exceptional Children, Ohio Department of Education, at 614.728.4582 or via email at: Ashley.Hall@education.ohio.gov.

For more information about the OLi4 and how to participate, contact Pamela VanHorn, PhD, Project Coordinator, University of Cincinnati Systems Development & Improvement Center, 3246 Henderson Rd., Columbus, OH 43220 at 614.897.0020 or via email at vanhorpm@ucmail.uc.edu.

For more information about the OLAC and OIP resources, contact Dr. Jim Gay, OLAC Co-director, at jimgay@basa-ohio.org; or Karel Oxley, OLAC Co-director, at Oxley@basa-ohio.org.