Inclusive Instructional Leadership: Acting on Ohio's Commitment to Improve Core Instruction and Learning Outcomes for EACH Child

Inclusive Instructional Leadership: Acting on Ohio’s Commitment to Improve Core Instruction and Learning Outcomes for EACH Child

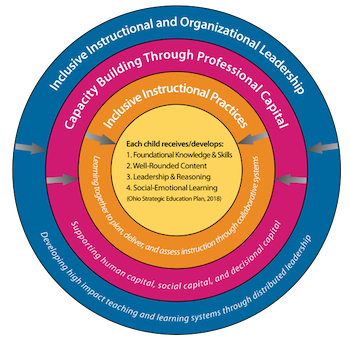

Ohio has long acknowledged the importance of leadership focused on improving learning outcomes for all students. Inclusive in its nature, this type of leadership requires all adults in an education system to share responsibility for the learning and well-being of each child in each classroom in each school across the system.

Inclusive instructional leadership is leadership that keeps the instructional core at the center of the district’s work, uses focused goals and strategies and engages all adults across the system to build system-wide capacity, attends to equity across all aspects of the district operation, and uses inquiry processes and evidence to inform decision-making.

Key to inclusive instructional leadership is the need for districts to focus and organize their work to ensure that each child has access to high quality core instruction and additional supports as needed in order to be “challenged to discover and learn, prepared to pursue a fulfilling post-high school path and empowered to become a resilient, lifelong learner who contributes to society (Each Child Our Future, ODE, 2019, p. 9).

“The concept is that all means all. We have lots of interventions but we believe that there’s no way we can intervene our way to high quality programming; our Tier 1 core instruction must be outstanding and it must be accessible. We have to be great with all students the first time around,” said Dr. Josh Englehart, Superintendent of Painesville City Local School District.

Located in northeast Lake County, Painesville City Local serves about 3,000 students in a preschool and five school buildings: three elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school. The district is highly diverse, with over half of the student population identified as Hispanic, another 18 percent identified as Black, and over 99 percent identified by the state as economically disadvantaged. A quarter of the student population is characterized as English learners, and 18 percent are identified as students with a disability.

The mission of the Ohio Leadership Advisory Council (OLAC), established in 2007 as a collaborative statewide effort jointly coordinated by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) and the Buckeye Association of School Administrators (BASA), is to support Ohio school districts in building their capacity to provide strong core (aka Tier 1) instruction to improve learning opportunities and outcomes for all children.

OLAC identifies key areas of leadership practice necessary for district-wide continuous improvement on behalf of all children. At the same time, the Ohio Improvement Process (OIP) functions as Ohio’s primary improvement model applicable to all districts in the state, not only those districts identified as being in need of improvement. OLAC identifies the what of essential leadership practices and OIP provides a vehicle for operationalizing those practices on a system-wide basis through the use of aligned collaborative leadership teams: district leadership teams (DLTs), building leadership teams (BLTs), and teacher-based teams (TBTs).

We have lots of interventions but we believe that there's no way we can intervene our way to high quality programming; our tier one core instructions must be outstanding and it must be accessible. We have to be great with all students the first time around.

Josh Englehart, EdS, PhD

Superintendent

Painesville City Local School District

Research on district-wide improvement shows that certain strategies enhance performance and increase equity (e.g., Fullan, 2010; Seashore Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, 2010; Wahlstrom, Seashore, Leithwood, & Anderson, 2010). The OIP draws on this research, and in particular, on Fullan and Quinn’s (2016) model of district improvement and the Moving Your Numbers (MYN) studies (e.g., Maltbie, Morrison, Duan, & Dariotis, 2017; Telfer & Howley, 2014; Tefs & Telfer, 2013; Telfer, 2011).

A national validation study supported four leadership domains or strategies that supported earlier work to produce the Moving Your Numbers district self-assessment guide. These four strategy areas, which can be characterized as non-negotiable areas required for continuous district-wide improvement, are described by Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) scholars Stephen Anderson and Santiago Rincon-Gallardo (2021).

The four areas, detailed below, are: (1) promoting system-wide learning, (2) prioritizing the improvement of teaching and learning, (3) building capacity through support and accountability, and (4) sustaining an open and collaborative culture.

Using Research to Improve Implementation of Inclusive Instructional Leadership

Like Superintendent Englehart, Mad River Local Schools Superintendent, Chad Wyen, believes that using a research-based approach to meet the needs of all students inclusively is the priority of the district. “We prioritized the improvement of teaching and learning as the basis of our focused improvement strategy,” said Wyen.

“We had to flip the script; we were individualizing so much that our students weren’t getting full core, strong instruction. One of the first things we decided as a team was that there will be no students pulled from core instruction,” added Assistant Superintendent Krista Wagner.

Mad River Local, located in Riverside next to the city of Dayton and the Wright Patterson Air Force Base, serves close to 4,000 students across a preschool, four elementary schools, two middle schools, and a comprehensive high school.

Similarly, in Clermont-Northeastern (CNE) Local, in southwestern Ohio, Superintendent Michael Brandt relied on the use of evidence-based inclusive instructional leadership practices to establish aligned collaborative leadership and learning teams, focus the district’s work on the improvement of teaching and learning, and build the capacity of all adults across the district to work together to improve learning opportunities and outcomes for all children.

“It’s one thing to have someone go through a training one time. It’s another thing to build capacity,” explained Brandt. All principals participated in the Ohio Leadership for Inclusion, Implementation, and Instructional Improvement (OLi4) professional learning, which is grounded in inclusive instructional practices. “Participation allowed us to institutionalize our OIP model and the use of strong DLTs, BLTs, and TBTs,” added Brandt.

CNE, located in Batavia, serves about 1,400 students across three buildings (one elementary, one middle school, and one high school) in a largely rural area of Clermont County.

The SIPR as a common metric. In spring 2021, Painesville City Local, Mad River Local, and Clermont-Northeastern Local participated in a usability test of the web-based Systemic Improvement Practices Review (SIPR) instrument and accompanying discussion guide. The web-based version is being developed through the University of Cincinnati’s Information Technology Solutions Center (ITSC) and will be available statewide for district use in the coming year. Another rubric-style version will also be available for district use through OLAC in the coming year.

So, what’s the SIPR? It’s an assessment tool that districts – through their DLTs – can use to measure the scale of implementation across the district and the degree of implementation at any level of the system of the four domains of district leadership practice described above (i.e., promoting system-wide learning, prioritizing the improvement of teaching and learning, building capacity through support and accountability, and sustaining an open and collaborative culture).

Development of the web-based SIPR entailed a multi-year pilot (2018-19 and 2019-20) involving multiple districts from each SST region in the state, which established the tool’s reliability, validity, and usefulness in supporting district-wide continuous improvement. The resulting instrument produces a district-level measure by aggregating the ratings of individual DLT members who complete the web-based assessment instrument.

And the 2018-2020 two-year pilot followed a two-phase national validation study of the original instrument: the Moving Your Numbers (MYN) District Self-assessment Guide (Telfer & Glasgow, 2012). The two-phase validation, conducted in 2017, involved:

- Phase 1: an extensive expert panel review involving more than 20 experts – both researchers and practitioners from across the country – who reviewed the original Guide and made recommendations for how to reduce the number of domain and items and ensure the relevance of the tool for teams, rather than individual leaders. Conducted by the UC Evaluation Services Center (Maltbie, Morrison, Duan, & Dariotis, 2017), this phase of the pilot established the content validity of the instrument, resulting in a new and improved 53-item instrument that serves as a collective indicator of district-wide inclusive instructional leadership.

- Phase 2: an assessment of construct validity through a survey of 209 district leaders from across the country and factor analysis to assess relationships among the items. This phase, conducted by WordFarmers Associates (Howley, 2017) established the validity of three of the four domains that constitute inclusive instructional leadership. The fourth domain – sustaining an open and collaborative culture – was added after extensive work with and by the State Development Team (SDT).

The validation of the original MYN guide and the resulting SIPR assessment instrument and associated discussion guide provide solid research support for the OIP. They also provide districts with an easy to use, reliable, and valid way to identify their current level of implementation of inclusive instructional practices, and areas that need to be strengthened. In addition, the SIPR offers a common metric that, when used statewide, would provide important data and information that state leaders could use to identify and then address – through professional learning including coaching and technical assistance – common needs across the state.

Englehart describes the importance of inclusive instrucional leadership and how the SIPR supports district implementation this way:

The key link is building leadership; building leaders have to be capable and willing to lead not only the accountability to those practices, but also that ongoing coaching, that ongoing reflection in order to continue to build capacity. We’re using the SIPR in a very similar fashion to how we used the MYN guide – to conduct a thoughtful review and define, as part of our OIP plan, how we’re going to implement leadership practices. The SIPR guides us towards those ideas of how we can be better moving forward, no matter how effective we are. The SIPR widens the net of engagement and allows the team to draw on the perspectives of each individual member and then put all of that out in front of us and say, ‘ok, what does it mean?’ It prompts pre-reflection on the individual level before we really dig into the team-level reflection.

In CNE, Brandt recalls the early days of developing a system-wide culture of inquiry and learning. “We had no strategic plan and no sustained professional development. The results of our first MYN assessment were horrible; actually we were less than horrible! But we used the results and our experience with OLi4 to make personnel changes, to commit to OIP and develop strong aligned collaborative leadership teams, and to engage everyone in the work. The SIPR assessment includes the big factors that hold everything together and we use them as foundational pieces for continuing to improve everything we do.”

“Our focus is on shared accountability and equity for all students; there’s no reason to be looking at placing our students anywhere else because we provide better instruction thatn anybody in our area,” added TJ Dorsey, CNE’s Dean of Students.

Like CNE, Mad River Local used its experience with OLi4 and the MYN Assessment to rethink what Wyen calls their ‘end product’. “We rethought our goals and our use of OIP and really drilled down to what we needed to have in place as far as inclusive practices to move our numbers, and to move our kids, forward,” explained Wyen. That ‘drilling down’ naturally led to a focus on instruction and, based on the SIPR, to a “focus on prioritizing teaching and learning as the basis for our focused improvement strategy,” said Wagner.

“Our previous approach in English Language Arts was more of a whack-a-mole phonics approach; it was use whatever phonics you want, here’s your basal reader. Fast forward to today: we have a phonemic awareness program in place and LETRS PD for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grade teachers,”described Wagner. Similarly, in math, the district used the curriculum implementation framework to select materials, establish a common vision for instruction among stakeholders, and making Tier 1 instruction accessible to all learners.

“I always liked the MYN guide and thought it was a great reflective tool; it aligned with the work that were were doing as far as our OIP and our own self-evaluation of the gains we were making, but I didn’t think it aligned well with the decision framework. The SIPR has a lot more alignment and especially with the state’s new One Needs Assessment. It really gave us good feedback and information to use from the DLT to the BLT and truly assess our progress and needs. I’m excited to use it moving into next school year,” elaborated Wyen.

A focus on providing strong core instruction is a priority for all three SIPR usability test districts – Mad River, CNE, and Painesville City Local. And, at the heart of the work to improve instruction and make it accessible to every learner is the deep belief on the part of all three districts that high expectations for what each child can learn and achieve is essential in order to make meaningful improvements.

One example involves Mad River’s use of the Opportunity Myth report to change mindsets and longstanding assumptions about what some children can’t do. “We have issues sometimes because of the circumstances of our students’ home lives. We’ve used the Opportunity Myth to reinforce the need for core instruction to be grade appropriate so teachers aren’t teaching below grade level and busting through a lot of assumptions to focus on what children can and should do,” said Wagner.

Building System-wide Capacity

All three districts recognize the critical importance of high-quality professional learning that is job-embedded, sustained over time, and inclusive of ongoing support. “Our OIP team structures are being used to support job-embedded PD and to make sure we don’t have all these programs existing in silos; they’re all interconnected,” stated Wagner.

Known for his experience in engaging educators in meaningful professional learning, Brandt incorporated CNE faculty involvement as DLT, BLT, and TBT members into the district budget in order to institutionalize and elevated the importance of sustained collaborative learning. Educators in the district apply for membership and are paid for their time, a process that is written into the negotiated contract. Brandt also built in additional PD days and time for teacher team collaboration. “This isn’t an hour at a time PD. Building in structures that allow people to collaborate has worked wonders for us,” remarked Brandt.

Effective PD means getting clear on the intended outcomes the PD is designed to achieve. “You can do all the professional development you want, but that’s only going to get you so far unless you can define what you want to be happening in the classroom,” offered Englehart.

The SIPR helps define practices and regional support through Ohio’s SST network is helping districts make the connections between implementation of inclusive instructional leadership practices and classroom instructional practice. In fact, inclusive instructional leadership practices, as defined above, constitutes one of three inter-related areas of practice that form the foundation of Ohio’s Statewide System of Support (SSoS), guiding the delivery of services by Ohio’s state support teams (SSTs).

The work of Ohio’s SSTs is directed by ODE and decisions about the intensity and duration of services provided are driven by a set of assumptions or non-negotiables, which include:

- Improvement is everyone’s responsibility.

- Improvement requires all components of the system (state, regional, district, school, classroom, community) to work together.

- Districts play a key role in improving outcomes for all students across the system.

- Fidelity of implementation of the right strategies to meet district needs is necessary and sufficient to achieve sustainable improvement on behalf of all students.

- All SST functions (e.g., services related to special education, early learning, literacy, etc.) should be delivered in a coherent fashion using the OIP improvement framework.

- A unified statewide system of support requires the intentional use of a consistent set of tools and protocols (e.g., support documents) by all state-supported regional providers (rather than allowing for multiple approaches across the state, based on preference).

According to Englehart, what’s often missing in improvement efforts are indicators of implementation. “We receive plenty of information and resources from the state but where there’s still a gap is in how we can take often nebulous concepts, such as culturally responsive pedagogy, and inclusive instruction, and actually operationalize them. We understand the concepts, but if I’m going to have any reasonable assurance that we, as a system, can implement them, I need more than a conceptual understanding,” explained Englehart.

SSTs bridge that knowledge to practice gap – between helping districts understand the concept or models or frameworks that support improvement, and understand how to act on the concept in order to change practice across the system. The SIPR Discussion Guide supports the effective use of inclusive instructional leadership practices by delineating acceptable forms of implementation, and scale of implementation, as illustrated in the excerpt here. “Our SST is not a compliance arm; it’s a value-added relationship,” explained Englehart. “The greatest impact they’ve had in terms of the development of leadership systems based on inclusive practices is in the coaching they provide to understand the essential practices and to support the real systematic implementation of those practices. Our SST consultant is as good a model, if not the best model, of effective coaching that I’ve seen,” he added. Painesville City Local is supported by SST Region 4.

Like Englehart, Wyen also wanted real examples of what implementation should look like when done well prior to using the SIPR. “We struggled at first because we wanted to see examples. But we realized it was nice to complete the assessment first without that and then to use the discussion guide to really dive in and have the conversation,” explained Wyen. “The tool helps structure the conversation, but the conversation is the really important part.”

The SIPR assessment instrument and discussion guide will be available for district use some time in the coming year. Districts are encouraged to reach out to the districts featured in this issue of Cornerstone Connections or to OLAC for additional information.

Resources

Anderson, S. E., & Rincón-Gallardo, S. (2021). Learning to lead school districts effectively: A review of the literature. University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Fullan, M. (2010). All systems go: The change imperative for whole system reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts and systems. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Howley, A. (2017). Moving Your Numbers (MYN): Instrument validation study phase 2 report. Albany, OH: WordFarmers Associates.

Maltbie, C., Morrison, A., Duan, Q., & Dariotis, J. (2017). Evaluating the evidence base for using the Moving Your Numbers (MYN) district self-assessment guide for technical assistance: Key results from phase 1. Cincinnati, OH: Evaluation Services Center, University of Cincinnati.

Seashore Louis, K., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K. L., & Anderson, S. E. (2010). Investigating the links to improved student learning. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement.

Telfer, D. M. (2011). Moving your numbers: Five districts share how they used assessment and accountability to increase performance for students with disabilities as part of district-wide improvement. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Telfer, D. M., & Glasgow, A. (2012). District self-assessment guide for moving our numbers: Using assessment and accountability to increase performance for students with disabilities as part of district-wide improvement. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.movingyournumbers.org/images/resources/81157-self-assessment.pdf.

Tefs, M., & Telfer, D. M. (2013). Behind the numbers: Redefining leadership to improve outcomes for all students. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 26(1), 43-52.

Telfer, D., & Howley, A. (2014). Rural Schools positioned to promote the high achievement of students with disabilities. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 33(4), 3-13.

Wahlstrom, K., Seashore, K., Leithwood, K., & Anderson, S. (2010). Learning from leadership: Investigating the links to improved student learning. Research Report Executive Summary. Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement. University of Minnesota

For More Information

For more information about the districts featured in this issue of Cornerstone Connections and how they’re using inclusive instructional leadership practice to provide equitable opportunities to learn for each child, contact:

Michael Brandt, Superintendent, Clermont Northeastern Local Schools, at brandt_m@cneschools.org or by phone at 513.625.1211.

Chad Wyen, Superintendent, Mad River Local Schools, at chad.wyen@madriverschools.org or by phone at 937.259.6606.

Josh Englehart, EdS, PhD, Superintendent, Painesville City Local Schools, at josh.englehart@pcls.net or by phone at 440.392.5060.

For more information about resources to support districts during the pandemic and beyond, contact Dr. Jim Gay, OLAC Co-director, at jimgay@basa-ohio.org; or Karel Oxley, OLAC Co-director, at Oxley@basa-ohio.org.

NOTE: Specific products/programs referenced are ones used by the districts featured in this article; however, OLAC does not endorse any particular product/program.