Instruction that Makes a Difference for Every Learner: Focus on the Use of Inclusive Instructional Practices - Part I

Over the course of the 2018-19 school year, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) sponsored a collaborative initiative intended to reframe the work of Ohio’s statewide system of support (SSoS). Partners in this initiative were personnel from various offices within the ODE, directors of Ohio’s 16 state support teams (SSTs), and staff from the University of Cincinnati Systems Development & Improvement Center. The partnership went by the name State Development Team (or SDT).

The overarching aim of the SDT was to reset the focus of regional services in ways enabling them to provide better and more coherent support to school districts, community schools, and other educational organizations. Grounded in Each Child, Our Future – Ohio’s Strategic Plan for Education: 2019-2024, the reframed regional system will help educators meet the needs of each child in the state.1

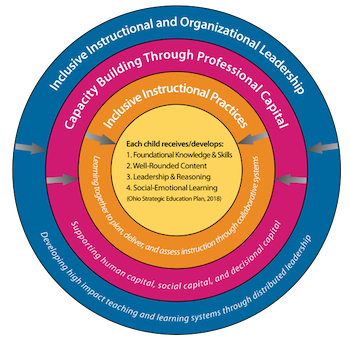

The SDT examined recent, high-quality research as a basis for identifying key areas of practice shown to be essential to supporting districtwide continuous improvement in teaching and learning for all students. Three areas of practice proved to be especially important: (1) use of inclusive instructional and organizational leadership, (2) capacity building through professional capital, and the (3) use of inclusive instructional practices. Deployment of evidence-based practices from these three inter-related areas enables districts, community schools, and other education organizations to ensure that every child, regardless of characteristics or labels, is provided equitable opportunities to learn, strong core instruction, and the services and supports needed to achieve higher and deeper levels of learning.

Making Instructional Practices Inclusive

Districts that are committed to providing equitable opportunities to learn for every child work to support every teacher in every classroom in every school throughout the district. The goal is to build all teachers’ capacity to use a variety of effective instructional practices and assess their impact on student learning.

The instructional practices that teachers use have a strong and direct influence on students’ learning; however, even though positive effects have been associated with numerous practices, not all work well with every student or in all contexts (Ball & Forzani, 2009; Hattie, 2009; Rowan, Correnti, & Miller, 2002; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001; Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014; Tomlinson, 2017) (Ohio Department of Education, 2019, p. 29).

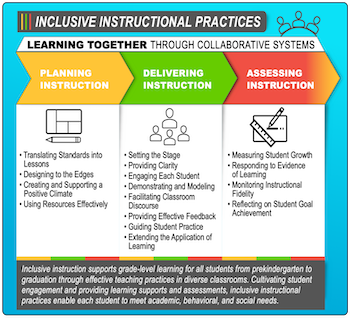

As SST 5 Director, Michele Moore noted, “We really focus on the services that are provided to each and every learner every day. One of the areas we, as SSTs are focusing on, is thinking through how we plan, deliver, and assess instruction using collaborative structures.” Moore is Director of State Support Team Region 5, which is operated through the Mahoning County Educational Service Center in northeast Ohio. It serves districts, community schools, and other education organizations in Mahoning, Trumbull, Ashtabula, and Columbiana counties.

Each of these areas of teaching practice – planning, delivering, and assessing instruction – involves intentional actions grounded in evidence. These actions are illustrated in the sidebar to the right. All are needed to give each student a high-quality education: strong core instruction in the general education curriculum.

Learning to use effective practices with fidelity is the key to effective teaching. But teachers don’t need to learn these practices on their own. “We know that, individually, teachers work on behalf of all students, but the power is in the team. So, the importance of the teacher-based teams working, planning, and delivering instruction to all learners is a critical piece of the work. We also know this doesn’t happen without support from effective leaders who take intentional steps to meet the needs of each learner in their school district,” added Moore.

From “Inclusion” to Inclusivity

“The inclusive in inclusive instructional practices is about using practices that enable each student to meet academic, behavioral, and social needs,” said Moore. But the use of inclusive practices is not the same thing as inclusion. It draws on a broader view of equity; it links quality instruction with equitable outcomes.

The shift from a narrow focus on inclusion to a broader commitment to inclusivity in all aspects of the district’s work characterizes the systemic change that is taking place in the Struthers City School District. The district’s community-based strategic planning process illustrates the district’s commitment to inclusivity.

Described by Superintendent Pete Pirone as a “strong blue-collar community that is passionate, supports our schools, and is progressive in its commitment to offer an array of offerings and technology to all of our students,” the district’s renewed mission is to serve our community by offering rigorous, diverse, and quality learning opportunities while developing the abilities of each child so they can become independent, life-long learners who positively impact society.

“Our belief statements really fit the philosophy of inclusive practice; we believe that all students should have equal access to a high-quality education with a rigorous curriculum, state of the art technology and facilities, and challenging instructional practices to prepare them for diverse career paths,” explained Pirone.

Not far from Struthers, the Niles City School District is at work to improve the quality and consistency of instruction provided to all learners. According to Niles Superintendent Ann Marie Thigpen, inclusive instructional practices is about “teaching for all students.”

“At the district level, Niles City Schools has had a transformation with regard to inclusive instructional practices. We started about five years ago with fragmented teacher-based teams and non-functional district and building leadership teams that focused on compliance. Now, because of the support from SST 5 and the work we’ve done through the early literacy pilot, we’ve moved our district in a direction of co-planning for all students on a daily basis,” Thigpen explained.

Niles City Schools serves about 2,200 students in kindergarten through grade 12 in four schools: Niles Primary School (grades K-2), Niles Intermediate School (grades 3-5), Niles Middle School (grades 6-8), and Niles McKinley High School (grades 9-12). Struthers City Schools serves approximately 1,760 students, kindergarten through grade 12, in three buildings: Struthers Elementary School (grades K-3), Struthers Middle School (grades 4-8), and Struthers High School (grades 9-12).

"Accepting all of the children from our community is really important to our staff. We know that our families need us, and we need them as well"

Amanda McNinch

Coordinator of Special Services

Struthers City School District

Both districts report close to 80% of their students as economically disadvantaged and between 13 and 14% as students with a disability. Niles and Struthers, like other districts in the greater Youngstown area, have experienced decreasing enrollment. Thigpen reported, for example, that Niles’ “enrollment dropped by 600 children in the last 10 years.”

Making sure everyone counts. Personnel from the Struthers and Niles city school districts believe that a commitment to inclusivity extends beyond the school walls to the larger school community.

“Our goals and our mission are coming not just from the educational side, but from our community. When we talk about meeting the needs of all students, our community is well involved and passionate about the district. We not only have educational support for the changes in practice we want to make, but we also have parental, community-based support; it’s their voice too. I think that’s vital because our parents are craving to see all kids grow,” said Bethany Carlson, Principal of Struthers Elementary School, and one of the district’s internal OIP facilitators.

“Our families, parents, teachers, and administration feel a responsibility to help our community grow as far as economics, and have our children be employable within our community or nearby. Our teachers know generations of families and don’t just see education as a job that they do but truly as a service that they provide. Accepting all of the children from our community is really important to our staff. We know that our families need us, and we need them as well,” added Amanda McNinch, Coordinator of Special Services for the Struthers City School District.

This perspective fits well with what research says about family and community engagement. Joyce Epstein, long recognized as an expert in the development of family-school partnerships, asserts that “all programs of school, family, and community partnerships are about equity.” (2019, p. 2)

“Equity means that all students have the opportunity to learn, all students have access to strong core curriculum based on their grade level, and all students have access to all teachers; that’s equity,” offered Thigpen. “At Niles City, we’re very open to hearing one another, to making effective decisions and different decisions to improve the quality and inclusiveness of the instruction we provide to each child,” she added.

For more information about strategies for involving parents and community members as partners in the education of all children, learn about Family and Community Engagement.

Strong core instruction for all. Personnel from Struthers and Niles view inclusive instructional practices as the foundation for the strong core instruction that is provided to all children. In particular, efforts to improve literacy, especially in the elementary grades, has positioned both districts to build the instructional capacity needed to meet the needs of diverse learners.

“Using inclusive instructional practices as a framework is foundational for us. We don’t just focus on special education students but use that framework to impact all students by deepening our understanding of inclusive instructional practices, embedding their use as the basis for instructional changes and decisions, and threading them through all professional development,” said Carlson.

With support from SST 5, Struthers personnel have been able to benefit from the Mahoning County Striving Readers Consortium. “Based on what we learned through the State Support Team Literacy Academy about the Simple View of Reading2, we’ve focused on explicit instruction, provided Heggerty3 training, and written a School Quality Improvement Grant that embeds a focus on explicit instruction across all grades. All of this work goes back to what we’ve been able to learn because of the support from SST 5,” added Carlson.

“Struthers City Schools always attends our peer-to-peer networks and one of the things that makes them stand out is that their superintendent, Mr. Pirone, attends and is an active member with their leaders. They share their learning with other districts in our region and always go back and implement with fidelity the practices that match their needs in a way that’s contextualized for Struthers,” explained Moore who is pictured (from left to right) with Bethany Carlson, Pete Pirone, and Amanda McNinch.

Niles City Schools participation as an Early Literacy Pilot district has had a significant effect on the quality of reading instruction and the ways in which educators work together to meet students’ instructional needs. Ohio’s Early Literacy Pilot supports 15 high-need districts in implementing evidence-based language and literacy strategies as part of their universal instruction and interventions. The pilot serves as the foundation for the design and implementation of evidence-based strategies contained in Ohio's Plan to Raise Literacy Achievement.4

“We’ve seen our teachers use the instructional practices they’re learning with fidelity. Our Title I teachers, intervention specialists, and regular classroom teachers are all working collaboratively at the same time with groups of students,” said Thigpen. At the intermediate level, Principal Christopher Staph added, “we’re addressing the needs of all students by using an inclusive model. At Niles Intermediate, our goal is literacy and providing a strong foundation so that all students are able to access content as they go forward” said Staph.

At the middle school level, teachers are content- and standards-driven and we had a consistency concern that needed to be addressed across all content areas and all grades,” explained Assistant Principal Allyson Martin. “We noticed that a group of students still had gaps in kindergarten through third grade reading levels and we’re using our Striving Readers Grant to address gaps and improve consistency in instruction, she added.

Thigpen reflected, “K12 literacy is a goal for the district. It has taken focused effort year after year to build upon what we’re doing and learning through the early literacy pilot. Now with two other grants, we’re supporting true conversations about literacy at the middle and high school level.” In addition to the Striving Readers Grant, Niles was awarded in spring 2019 a School Quality Improvement Grant that will be used to provide intensive professional development in adolescent literacy.

Taking the Long View

“SST 5’s support has changed our educational lives. They’ve been that model of inclusivity for our teachers and our administrators by using the language of inclusivity, the language of differentiation, and the language of social justice in the professional development they provide. Inclusivity, especially at early ages, is going to benefit not only the children who are included, but also the children who are in the general education population and the children who are going to learn with them throughout the years,” offered McNinch.

“I think it’s important when you talk about inclusive practices, a lot of times we’ll focus on the academic and the behavior, but the social benefits, being with same-age peers, is also something that cannot be overlooked,” said Pirone. Staph agrees, noting “the social aspect – how teachers talk to students, how students talk to teachers – is very important for our kids to succeed.”

“As a superintendent, you have to find a focus, a focus that fits kindergarten through grade 12, and that is often difficult. For us, the focus is literacy. I remember sitting back five years ago and the overwhelming feeling to have to move 267 teachers and a support staff of about 90. Five years ago, I could say ‘I’m not sure how we’ll get there.’ But, the support we’ve received has allowed us to be where we are today. So, it grows. It’s exciting, and it will be exciting to see where we will go in the next five years,” reflected Thigpen.

Part II of Instruction that Makes a Difference for Every Learner: Focus on the Use of Inclusive Instructional Practices, will appear in the winter 2020 issue of Cornerstone Connections.

Annotations

1 Each Child, Our Future

2 For more information about the Simple View of Reading, go to: https://www.improvingliteracy.org/resource/learning-to-read-the-simple-view-of-reading

3 Heggerty training refers to professional development in phonemic awareness using a curriculum developed by Dr. Michael Heggerty.

4 See the Summer 2019 issue of Cornerstone Connections for more information about Ohio’s investment in improving literacy outcomes for all children: /view.php?cms_nav_id=188

References

Baker, S.K., Fien, F., Nelson, N. J., Petscher, Y., Sayko, S., & Turtura, J. (2017). Learning to read: “The simple view of reading”. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy.

Ball, D., & Forzani, F. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511.

Epstein, J. (2019). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H.., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST.

Resetting the foundation of Ohio’s statewide system of support (SSoS). (2019). Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education.

Rowan, B., Correnti, R., & Miller, R. (2002). What large-scale survey research tells us about teacher effects on student achievement: Insights from the Prospects study of elementary schools. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Ohio Department of Education. (2019). Each child, our future. Ohio’s strategic plan for education (2019-2024). Columbus, OH: Author.

Ohio Department of Education. (2018). Ohio’s plan to raise literacy achievement: Birth through grade 12. Columbus, OH: Author. Retrievable from http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Literacy/Ohios-Plan-to-Raise-Literacy-Achievement.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US.

For More Information

For more information about SST 5 and how regional personnel support districts, contact Michele Moore, Director, SST 5, at 330.533.8755 or via email at michele.moore@sstr5.org.

For more information about Struthers City School District, contact Superintendent Pete Pirone at 330.750.1061 or via email at pete.pirone@strutherscityschools.org.

For more information about Niles City School District, contact Superintendent Ann Marie Thigpen at 330.989.5095 or via email at annmarie.thigpen@nilesmckinley.org.

For more information about Ohio’s literacy initiatives, contact Melissa M. Weber-Mayrer, PhD, Director, Office of Approaches to Teaching and Professional Learning, Ohio Department of Education, at 614.728.8095 or via email at Melissa.Weber-Mayrer@education.ohio.gov.

For more information about the OLAC and OIP resources, contact Dr. Jim Gay, OLAC Co-director, at jimgay@basa-ohio.org; or Karel Oxley, OLAC Co-director, at Oxley@basa-ohio.org.