Understanding by Design, Page 2

In science, for example, one powerful idea is that experiments and their results must be replicable in order to be accepted as useful or true. However, is this idea more powerful than the idea of the provisional nature of scientific knowledge or the idea that all organisms require a supply of energy? In history, a big idea is that major events, such as landing astronauts on the moon, have many causes. Is that big idea more important than the idea that there are multiple interpretations of past events?

In deciding which big ideas are the key concepts for standards at their grade level, teachers may need other criteria in addition to the power of the idea. Understanding by Design offers another criterion for selecting big ideas: Big ideas should engage students’ interest.

Once teachers have identified the big ideas that seem most appropriate for the students in their classroom, they can begin to think about how students could demonstrate that they have developed an understanding of the ideas. By “understanding” big ideas, Wiggins and McTighe mean students can do one or more of the following:

- explain the idea,

- interpret the idea,

- apply the idea,

- take different perspectives on the idea,

- show empathy for different perspectives on the idea, or

- recognize their own perspective on the idea.

As you may have noticed, the UBD definition of “understanding” is broader than some other definitions (e.g., Benjamin Bloom’s well-known definition). Wiggins and McTighe use the term “understanding” to mean “applying,” “interpreting,” and “evaluating” as well as simply “comprehending.”

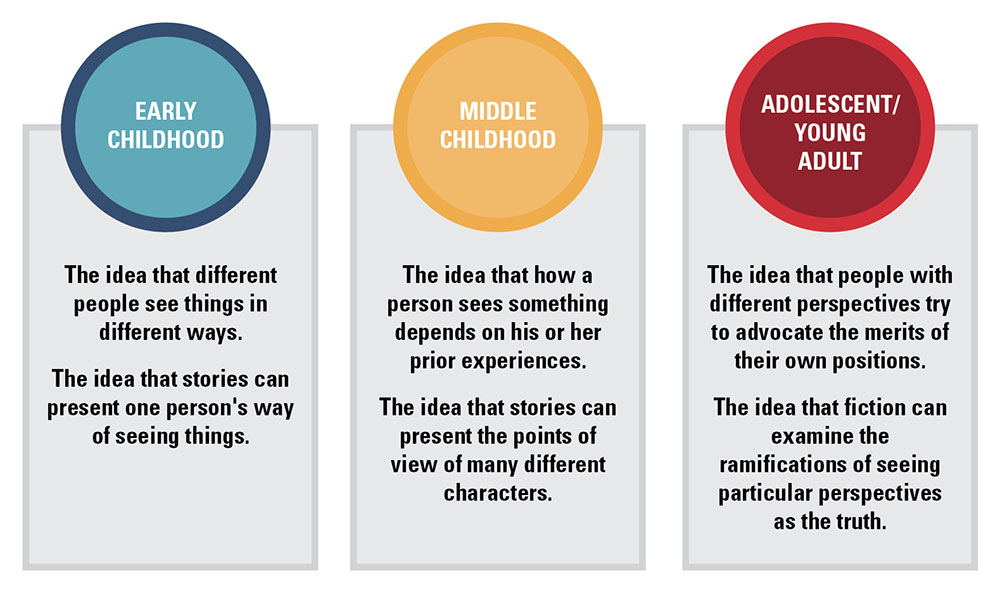

Of course, teachers wouldn’t expect early-childhood students to grasp big ideas with as much depth or breadth as high-school students would. Consider, for example, the concept of “perspective-taking” as an approach to understanding fiction or persuasive writing. How might teachers help students of different age levels think about the concept? The graphic below provides some suggestions.

One of the major curriculum features of UBD is the essential question. An essential question should foster critical thinking, spark curiosity, and engage students in inquiry (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). An early-childhood teacher might ask, “Can words hurt people?” or “How does being a spider influence the way Charlotte views the world?” These types of questions are likely to stimulate students to think about perspective-taking.

With UBD, questions are also essential to every phase of the curriculum-design process. Davidovitch (2013) has identified four broad questions that help teachers design curriculum that takes learners’ prior knowledge and experiences as well as their interests into account. The graphic below illustrates these questions and provides guidance about how to address them.

This Foundational Concept can be found in the following module pages:

- Curriculum, Designing and Developing Curriculum